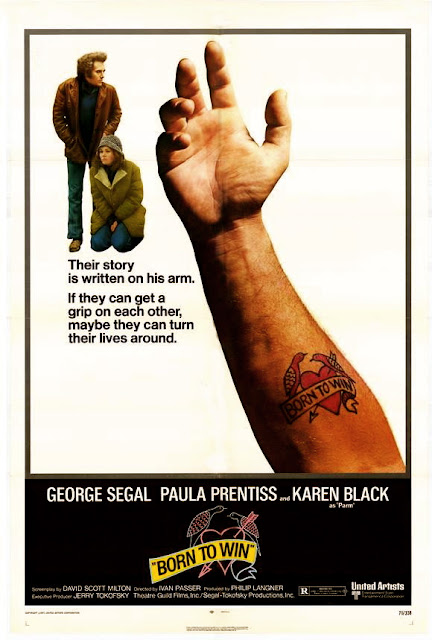

It’s impossible to completely dismiss Born to Win, a would-be comedy about heroin addiction, even though the film is a disaster from a tonal perspective and not especially satisfying from a narrative perspective, because the film’s saving graces include gritty performances by several actors and a great sense of place. So, while Born to Win is laughable compared to the same year’s The Panic in Needle Park, a truly harrowing take on the same subject matter, Born to Win isn’t an outright dud. George Segal stars as J, a former hairdresser who has fallen into petty crime as a means of supporting his habit. Over the course of the story, J embarks on a new romance with Parm (Karen Black), a rich girl with a taste for dangerous adventure, and he gets into a complicated hassle with his dealer, Vivian (Hector Elizondo). The romantic stuff with Parm defies logic right from the beginning—Parm discovers J trying to steal her car, but instead of calling the police, she takes him to bed. Huh? The drug-culture material is more believable, especially when two cops (one of whom is played by a young Robert De Niro) coerce J into helping them entrap Vivian. In general, the seedier the scene in question, the more watchable Born to Win becomes. For instance, one of the best sequences involves J sweet-talking a mobster’s wife by pretending he wants sex, when in fact he’s simply trying to enter the mobster’s apartment for purposes of robbery. Segal’s not the right actor for this story—he’s too charming and urbane—but it’s interesting to imagine the circumstances by which a character fitting Segal’s persona might have fallen into such desperation. Had Born to Win focused on J’s descent (and had the filmmakers not opted for such a glib treatment of addiction), the picture could have had impact. Alas, director/co-writer Ivan Passer fumbles, badly, by attempting to merge black comedy with inner-city tragedy, and his undisciplined storytelling is exacerbated by a truly horrible music score. Predictably, De Niro (whose role is inconsequential) and Elizondo fare best in this milieu, while Black and costar Paul Prentiss barely register. Yet the real star of the movie, if only by default, is New York City, with the dirty streets of Manhattan amplifying the film’s implied theme of lost souls getting chewed up by an unforgiving universe.

Born to Win: FUNKY